Expensive Paper Tigers - Part 2: Small Arms, Big Issues

There are no lessons being learned from 21st century warfare in our weapons acquisitions.

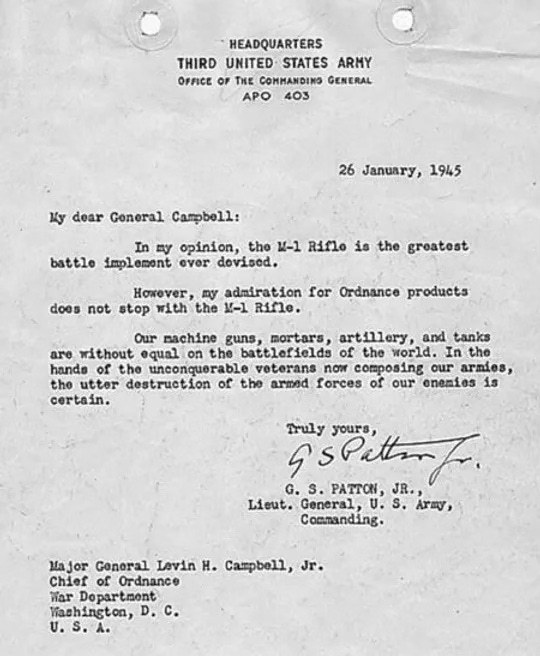

In the 1958, the United States government-owned Springfield Armory began producing the M14 rifle. It was essentially a warmed-over derivative of John C. Garand’s M1 rifle design from the 1930s that became famous as the first standard-issue service rifle issued to a military. The “U.S. Rifle, Caliber .30, M1” would serve with distinction in the Second World War, earning praise from its users and respect from America’s adversaries. General George S. Patton infamously described it as, “the greatest battle implement ever devised.” The M1 would go on to serve adequately in Korea, but even before that, it was beginning to show its age.

Prototypes of a product-improved M1 variant (known as the T20) that employed a detachable box magazine were being developed in 1944. The M14 rifle that first rolled off the assembly lines twelve years later was functionally identical to the T20 prototype in most respects save for one: The caliber. The T20 utilized the M1’s venerable .30-06 cartridge while the M14 was chambered for the now-ubiquitous but then-new 7.62x51mm NATO (.308 Winchester, in commercial parlance). The 7.62 NATO round used the same projectile as the .30-06 that it replaced, but in a shorter overall cartridge case.

There was a lot of drama surrounding the 7.62 NATO round. After WWII, scores of evaluations of small arms engagements were conducted by everyone left standing. Captured German reports were studied by the Allies (and the Soviets) and compared two the conclusions of their own researchers. The consensus was unambiguous: Small arms engagements were typically conducted at ranges way, way inside the performance envelope of the lethal-to-a-thousand-yards full power rifles that were the staple service weapon of the infantryman. Most firefights happened between fifty to a hundred and fifty yards, with the rare instance of an engagement out to maybe three hundred yards.

The ramifications of this were not lost on military planners, ordnance officers, or weapons designers. Rifle calibers could be reduced in size, weight, and power without negatively impacting infantry lethality at realistic combat distances. And doing this would allow for the individual solder to carry more ammunition at the same time to boot. The Soviets rolled out the 7.62x39mm Soviet round and the SKS and AKM service rifles, relegating their ancient Mosin-Nagant 7.62x54mmR rifles to ceremonial use. The British adopted a shockingly forward-thinking bullpup service rifle called the EM-2, chambered in the equally ahead of its time .280 British caliber.

And the Americans were absolutely having none of that.

A couple of things led to the creation of 7.62x51mm: An insistence that all signatories to the North Atlantic Treaty utilize common calibers of ammunition* and the bull-headed insistence that the average conscripted American infantryman should be able to employ a rifle that was effective out to outlandish distances. Hence, the .30-06 cartridge was shortened somewhat, loaded to pressures intended to minimize the performance drop-off of the reduced case volume, and the 7.62mm NATO round was born. Nevermind that other allied nations had already fielded a much lighter, more practical round!

*Our insistence that everyone use standard calibers was strained, somewhat, by our stubborn refusal to switch away from the .45 ACP service pistols that we had been using since 1911 in spite of 9mm Parabellum being the standard NATO service pistol caliber. We wouldn’t change pistol calibers until 1985 with the adoption of the M9 service pistol.

Everyone else was forced to change, and by 1954, NATO was a 7.62x51mm bloc. Big, heavy battle rifles from the “right arm of the free world,” the FAL to the Spanish CETME and its closely related German sibling, the G3 and the American throwback M14 were the order of the day.

Hopes for the M14 were high, but initial testing of the prototypes was not inspiring. A version of the Belgian-designed FAL known as the T48 generally outperformed the Springfield Armory-based designs up until a series of arctic tests in which the M14 prototype was specifically babied and modified to succeed. The FAL-based prototype was not, and as a result, the Arctic Test Board rejected the T48. The writing was on the wall: The domestic design was going to be adopted. And it was. Despite the FAL’s often-superior performance in the 1956 tests, the M14 was eventually adopted.

In a move that would prove to be the shape of things to come, the M14 was marketed as a replacement for everything from the M1 rifle that it so closely resembled to the Browning Automatic Rifle, M3 Grease Gun submachine gun, M1 carbine, and even some pistols and sniper rifles. What an incredible value! A service rifle that is also an SMG, a handgun, a designated marksman’s rifle, and an LMG!

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before: It wasn’t particularly good at any of those things.

The M14 was a product-improved version of a design from a different era. And in a world in which the Soviet Union was mass producing Kalashnikov rifles, the M14 was basically obsolete the very day that it was adopted. The AKM was substantially lighter and several inches shorter, making it much more handy—especially at close quarters. It held 33% more ammunition per magazine. It was radically easier to control when fired in automatic mode. And all of this became inescapably obvious when Americans found themselves fighting Kalashnikov-equipped Vietnamese.

By the early 1960s, the numerous shortcomings of the M14 were impossible to paper over anymore. The light machine-gun version never became controllable enough to bring to production. It was always facially absurd that it would replace SMGs or select-fire carbines for use in confined spaces. And the advantages that it had over the AKM in range and practical accuracy at distance were illusory in jungle and urban combat. The AR-15-based M16 replaced the M14 as the standard-issued service rifle in 1964. It was the shortest-lived standard-issue American service rifle in history, and the NATO standard caliber that it ushered in and then ushered out was a point of serious consternation. Americans had to start losing men in war to disabuse themselves of the notion that a big, heavy, full-powered rifle cartridge that was lethal out to a thousand yards made any sense for the realities of infantry combat.

So, why the history lesson on the M14? Because I swear to God, the U.S. Army is doing the exact same thing all over again right now, today, but at exponentially greater cost. The Army appears to be full steam ahead with procuring a new and improved service rifle called the XM7 made by the suspiciously successful Sig Sauer. And this new wonder weapon will feature a totally novel, bespoke 6.8x51mm cartridge never before used in a weapons system. Why? To provide maximal body armor defeating capabilities at long ranges.

It’s a revised iteration of Sig’s MCX rifle—itself on its umpteenth undesignated iteration and now wearing the much cooler and certainly-not-focus-group-tested acronym name of “SPEAR”—from 2015. It’s shooting a full-power battle rifle cartridge that’s optimized for long range efficacy. And it’s in a caliber that nobody else on Earth uses. Sound familiar?

That’s right, boys and girls, it’s time to Learn No Lessons from the Last Time We Did This™.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Low Left to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.